Exploring the Conceptual Art Movement: History, Definition, and Evolution

Conceptual art, an influential art movement that emerged in the early 1960s, challenges traditional notions of art by prioritizing the conceptual over the visual. Within the realm of conceptual art, the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work, often transcending the physical manifestation of the artwork itself.

Artists such as Sol LeWitt and Marcel Duchamp are pivotal figures in the conceptual art movement, reshaping the landscape of contemporary art.

Unlike traditional art forms, where the focus is primarily on the visual aspects of the artwork, conceptual artists utilize a conceptual form to create art, emphasizing the underlying idea or concept.

This shift in focus from the tangible art object to the conceptual framework marks a significant departure from the conventions of modern art.

Conceptual artists employ various mediums, including installation art, performance art, and land art, to explore the nature of art and challenge established definitions. In the art world, conceptual art has sparked debates and discussions among scholars, historians, and critics, shaping the discourse on art history and contemporary visual art practices.

As many conceptual artists continue to push the boundaries of artistic expression, conceptual art remains a dynamic force in shaping the trajectory of contemporary art.

Overview

Understanding Conceptual art requires delving into its multifaceted nature, which can be more complex than other art movements.

The term “Conceptual art” encompasses various interpretations and contexts, making it easy to become bewildered by its usage.

While commonly associated with the art movement of the 1960s and 1970s in the United States, Conceptual art can be understood in different ways. What exactly does this term imply? When did Conceptualism emerge as an art movement, and does it persist today?

Conceptual art was first recognized in the late 1960s and continues to influence contemporary practice, as seen in the versatile exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art. In his extensive tome, “Conceptual Art,” art historian Paul Wood delineates the diverse usages of the term:

> Conceptualism often serves as a pejorative label for aspects of contemporary art that centre around conceptualisation rather than aesthetics.

> Conceptualism denotes the Anglo-American art movement flourishing in the 1960s and 1970s, wherein the idea, planning, and creative process held precedence over the final outcome.

> A broader interpretation of Conceptualism suggests that individuals worldwide have engaged in conceptual approaches since the 1950s, exploring themes ranging from imperialism to personal identity, thereby fostering a Global Conceptualism.

Conceptual art emerged during the 1960s as a critique of the prevailing modernist movement, which prioritised aesthetics.

Typically spanning from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, Conceptualism shifted the focus from technical proficiency and visual appeal to the primacy of ideas or concepts behind artworks.

Conceptual artists utilised diverse materials and forms to articulate their concepts, resulting in a wide array of artworks spanning performance, text, and everyday objects, highlighting how conceptual artists used unconventional means to express ideas.

They probed the boundaries of art as idea and knowledge, employing linguistic, mathematical, and process-oriented dimensions, as well as invisible systems and structures, in their creations.

Origins and Influences

Minimalism & Fluxus

Transitioning from the artistic landscape of the late 1950s, characterised by movements like Fluxus and Minimalism, the late 1960s marked a significant shift towards Conceptualism, denoting when conceptual art was first recognised as a distinct movement.

Fluxus, originating in the early sixties, shared kinship with Dada and emphasized the integration of art with life, utilizing found objects, sounds, and everyday activities as stimuli. Notable Fluxus figures such as Joseph Beuys, George Maciunas, and Yoko Ono advocated for embracing flux and change as fundamental aspects of existence.

Meanwhile, Frank Stella’s Black Paintings of the late 1950s challenged traditional notions by presenting the canvas itself as the artwork, a concept further developed by Minimalist artists like Donald Judd and Carl Andre in the mid-1960s.

Minimalism embraced abstract repetition and industrial fabrication, rejecting conventional materials and forms to explore the essence of the art object. This shift towards prioritizing the concept or idea behind the artwork laid the foundation for the emergence of Conceptualism, revolutionizing the trajectory of modern art.

Paragraphs on Conceptual Art

In 1967, Sol LeWitt, an artist renowned for his contributions to Conceptual Art, penned “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” a seminal text published in Artforum. Regarded by many as the movement’s manifesto, LeWitt’s words encapsulated a profound shift in artistic philosophy.

He asserted that in Conceptual Art, the idea or concept reigns supreme, transcending any aesthetic considerations. When an artist employs a Conceptual form, LeWitt contended, meticulous planning precedes execution, rendering the act of creation almost perfunctory.

He famously described the idea as a machine that generates art, underscoring the primacy of concept over material manifestation. This prioritization of concept over object directly challenged the prevailing theories of influential formalist art critics such as Clement Greenberg and Michael Fried.

Unlike their emphasis on the formal qualities of art objects, LeWitt championed the conceptual framework as the driving force behind artistic creation, marking a decisive departure from the aesthetic criteria of preceding generations.

Declaration of Intent

In 1968, Lawrence Weiner, an influential American Conceptual artist, further elaborated on Sol LeWitt’s ideas with his manifesto titled “Declaration of Intent.” Weiner boldly proclaimed his decision to abandon the creation of physical art, asserting that the mere idea behind a work was sufficient without the need for tangible manifestation.

In his declaration, Weiner outlined three options for the realization of a piece: construction by the artist, fabrication by others, or no physical construction at all. Each option, he argued, held equal validity, with the ultimate determination resting upon the receiver upon encountering the artwork.

Published in his inaugural book, “Statements” (1968), Weiner’s manifesto transferred the responsibility of interpretation from the artist to the viewer. “Statements” comprised solely of written descriptions of sculptures, detailing their materials and spatial relationships.

Weiner’s philosophy posited that the viewer could experience the artistic essence simply by reading these descriptions, thereby challenging the necessity of physical construction for Conceptual artwork to exist and resonate in the world.

Formation of Conceptual Art Movements

The emergence of Conceptual Art movements in the late 1960s saw a diverse array of international artists converging in New York, each harbouring unique perspectives on the role of contemporary art, founding what would later be recognised as the first conceptual art movement.

Despite their disparate ideas, a cohesive movement began to take shape within the city’s artistic landscape, particularly within institutions like the Museum of Contemporary Art, which played a pivotal role in promoting conceptual work.

In 1967, Joseph Kosuth curated the exhibitions Non-Anthropomorphic Art and Normal Art, showcasing works by himself and fellow artist Christine Kozlov. Kosuth’s assertion in the exhibition notes that “The actual works of art are the ideas” encapsulated the essence of Conceptual Art.

The subsequent year witnessed a series of Conceptual Art exhibitions organized by New York dealer and curator Seth Siegelaub, further solidifying the notion of a unified movement. In 1969, the Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted the exhibition Information, which brought together numerous Conceptual artists.

This event, though met with ironic skepticism, underscored the growing influence of Conceptual Art, despite its inherent criticism of institutionalized museum systems and market-driven interests, including critiques directed at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Global Expansion of Conceptual Artists

Conceptualism transcended geographical boundaries, finding expression in various parts of the world beyond the US and England. In Italy, the emergence of Arte Povera in 1967, a term coined by art critic Germano Celant, signaled a movement of Conceptual artists critiquing established state institutions.

Meanwhile, in France, Daniel Buren’s art during the 1968 student uprisings aimed to challenge the institutionalization of contemporary art by redirecting focus onto the exhibition context rather than the artwork itself.

In the Soviet Union, Boris Groys labeled a cohort of Russian artists active in the 1970s as “the Moscow Conceptualists” or “Russian Conceptualists.” Beginning with the Sots art of Komar and Melamid, this movement persisted as a subversive force well into the 1980s, with artists exploring various media, from painting to literature.

Internationally, collectives like Canada’s General Idea, comprised of Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal, and AA Bronson, engaged in politically charged ephemeral works and installations from 1967 to 1994, addressing issues such as the pharmaceutical industry and the AIDS crisis.

In Latin America, artists like Cildo Meireles in Brazil reclaimed the “readymade” concept with his Insertions into Ideological Circuits series (1969), stamping political messages onto everyday objects like banknotes and Coca-Cola bottles before returning them to circulation.

Additionally, groups like the Chilean CADA (Art Action Collective) and the Peruvian Parenthesis continued to employ Conceptualism as a tool for political critique. The legacy of Marcel Duchamp, with his groundbreaking ready-mades such as “Fountain,” challenging established conventions and prompting critical reflection on the nature of art itself, permeates the global expansion of Conceptual art, influencing artists like Meireles in Brazil who reimagined everyday objects as art.

The boundaries of art lie not in the physical materials or techniques employed, but in the conceptual framework that informs the artwork. This conceptual shift has sparked debates among art critics and scholars, prompting reevaluations of the very definition of art. Boris Groys, a prominent art critic, labeled conceptual art as “art after philosophy,” highlighting its departure from traditional aesthetic concerns towards more conceptual and intellectual terrain.

Major Artists and Influences

Marina Abramović, John Baldessarin, Mel Bochner, Ian Burn, Hanne Darboven, Jan Dibbets, Hans Haacke, Joseph Kosuth, On Kawara, Sol LeWitt, Mel Ramsen, Lawrence Weiner, Yoko Ono

Demystifying Conceptual Art: Unveiling its Defining Traits

Conceptual Art, unlike traditional forms, challenges the very essence of art by prioritising ideas and concepts over aesthetic appeal.

This revolutionary movement focuses on the dematerialisation of the artwork itself, stripping away tangible elements to convey profound messages, essentially providing a stark example of artist uses a conceptual form to communicate.

Take for example Sol LeWitt’s Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, in which he articulates that the idea behind a work holds more significance than its physical manifestation. This shift from material creation to intellectual exploration marks a pivotal departure from conventional artistic practices.

Moreover, artists like Yoko Ono epitomize this emphasis on conceptual brilliance rather than visual allure through pieces like Cut Piece.

By inviting audience participation in cutting away parts of her clothing until she decides to stop, it dismantles traditional notions of static artworks and highlights the interactive nature inherent in Conceptual Art.

These examples underscore how this avant-garde movement challenges viewers to engage with art on a cerebral level, sparking conversations beyond what meets the eye.

Through these distinct characteristics, Conceptual Art reshapes our understanding of creativity and pushes boundaries within the art world, embodying the definition of conceptual art by its very nature.

Exploring Conceptual Art: Ideologies, Expressions, and Critiques

Conceptual Art emerged as a movement that sought to transcend traditional artistic boundaries, resulting in a challenge to categorise it distinctly amidst the diverse artistic developments of the 1960s.

Conceptualism manifested in various forms, including happenings, performance art, installation art, body art, and earth art.

However, the common thread uniting these diverse expressions was the rejection of conventional methods of evaluating art, a defiance against the commodification of artistic creations, and the assertion that Conceptual Art could and should exist independently of these commercial influences.

By sidestepping traditional aesthetics, Conceptual Art defied easy stylistic classification, often appearing objective and devoid of emotion. This everyday appearance and the multiplicity of expression became defining characteristics of the movement.

At the forefront of Conceptual Art’s exploration of idea-based creativity was Joseph Kosuth, who developed a rigorous analytical model centred on the idea that art must continually interrogate its own purpose.

In his influential essay “Art after Philosophy” (1969), Kosuth challenged the necessity for traditional artistic media, questioning whether art required a visual or physical manifestation at all.

Lawrence Weiner and others echoed Kosuth’s sentiments, advocating for the abandonment of physical art objects. By minimizing the materiality of art, these artists aimed to strip away aesthetic considerations and remove art from the realm of commodity.

Art critic Lucy Lippard chronicled the dematerialization of the art object in her seminal work “Six Years: the Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972” (1997). Lippard argued that Conceptual Art provoked dispersion and voidance rather than conventional formation and creation.

Many Conceptual artistic ideas were open-ended propositions devoid of predetermined conclusions.

However, American artist Mel Bochner criticized Lippard’s interpretation as convoluted and arbitrary.

Lippard later contended that most accounts of Conceptualism were inaccurate, highlighting the unreliability of memories and spoken narratives surrounding Conceptual Art events, even among the artists themselves.

The Art of Language: Exploring Textual Expression

Although the integration of written text into artistic compositions was not entirely novel by the 1960s—text had appeared alongside visual elements in earlier movements such as Cubism—a notable shift occurred with artists like Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth, Ed Ruscha, and John Baldessari, who elevated text to the forefront of their visual creations.

Diverging from their predecessors, this new generation of artists often boasted academic backgrounds, a factor contributing to their embrace of intellectualism and the profound influence of twentieth-century linguistics studies.

Text-based artworks frequently employed abstract formulations, characterized by abrupt commands, ambiguous statements, or even solitary words, inviting viewers to form their own associations.

While pioneering Conceptualists like Weiner and Baldessari continue to make significant contributions today, they have also inspired a subsequent generation of artists, from Jenny Holzer to Tracey Emin, to further explore the potential of text-based practices and challenge conventional notions of art and its boundaries.

Challenging Institutional Norms: Conceptual Art's Anti-Commodification Stance

At the core of Conceptual Art lay a fundamental discomfort with the entrenched institutionalization of the art world, which had long served as the arbiter of “good” versus “bad” art.

Historically guided by market forces since the mid-nineteenth century, this system dictated that “good” art was marketable, while “bad” art was not, benefiting a select group of predominantly male and white artists, alongside members of elite social classes involved in art commerce and museum administration.

By the 1960s, it became evident to Conceptual artists and theorists that conforming to this system stifled avant-garde aspirations and impeded any meaningful challenge to the status quo.

As Conceptual artists scrutinised modern art practices of the era, they found the prevailing trends—abstract, post-abstract, and minimalist motifs—falling short of their radical aspirations.

In the words of Burn in a 1975 Artforum article, the reliance on concepts like “color,” “edge,” and “process” seemed insufficient for inciting real-world change, leaving artists feeling like mere manipulated puppets.

The late 1960s saw the emergence of a variant of Conceptualism known as institutional critique, championed by artists such as Hans Haacke, Michael Asher, Daniel Buren, and Marcel Broodthaers.

Institutional critique, while rooted in idea-based art, took the form of installations that implicitly challenged the assumed function of museums as mere preservers and exhibitors of masterpieces.

Instead, these installations cast a critical eye on the broader societal roles of museums—as arbiters of taste, investors, tax shelters, and gatekeepers of artistic success, a critique upheld by the evolving exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Crucially, institutional critique often unfolded within the very institutions being critiqued, complicating the relationship between artist and institution.

The success of these works often hinged on viewer participation, highlighting the interconnectedness of artists, viewers, and institutions within the art world.

Rather than outright rejection, Conceptual artists engaged in a nuanced interrogation of institutional norms, implicating themselves in the systems they sought to challenge.

Evolution of Conceptual Art: Redefining Boundaries and Inspiring Interdisciplinarity

Delving into the evolution of Conceptual Art unveils a dynamic landscape where traditional boundaries are blurred, and new possibilities emerge.

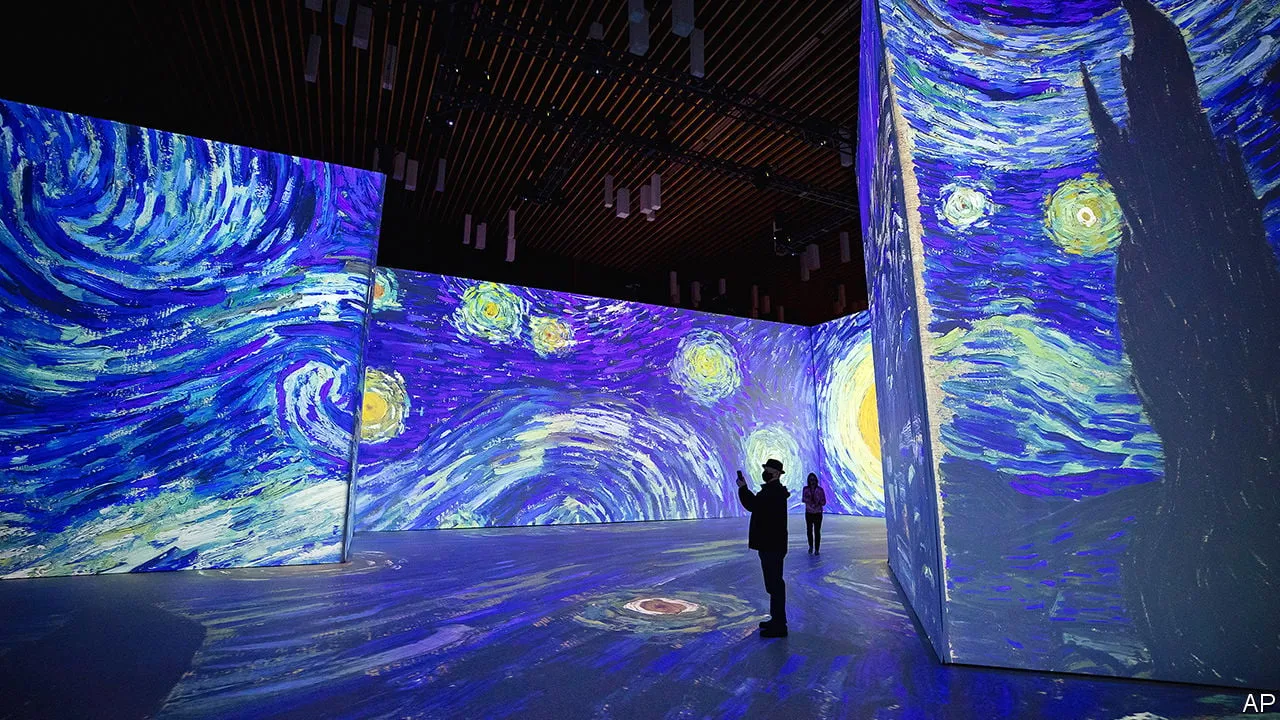

In contemporary iterations, artists have pushed the concept-based approach beyond conventional norms, embracing digital mediums, immersive technologies, and performance art to convey their ideas, indicative of how Art and Conceptual practices blend in the modern era.

This evolution not only challenges the perception of what art can be but also invites viewers to engage with multisensory experiences that transcend the limitations of traditional visual representation.

The shift towards interactive installations and participatory artworks reflects a deeper desire to forge meaningful connections between art, artist, and audience in a rapidly changing world.

Moreover, the impact of Conceptual Art extends far beyond the realm of visual arts, resonating with other artistic disciplines such as music, literature, dance, and even technology. Collaborations between artists from different fields have led to innovative projects that blend concepts from Conceptual Art with diverse creative practices.

By breaking free from medium-specific constraints and embracing collaborative approaches, these interdisciplinary explorations not only enrich each discipline but also foster a fertile ground for experimentation and hybrid creations that challenge established norms.

As Conceptual Art continues to influence various artistic domains, it inspires a reevaluation of how we perceive art’s role in society and its potential to connect disparate forms of expression in holistic narratives that transcend individual disciplines.

Subsequent Developments: Beyond the Era of Conceptual Art

While the model of Conceptual Art championed by Joseph Kosuth and Art & Language may be considered emblematic of the movement, other avenues of exploration emerged that were equally influential, showcasing the diversity of conceptual work.

Conceptual Art, by challenging conventions of craftsmanship and style, reinvigorated the focus on content, a facet that had been overshadowed during the dominance of formalist critique, thereby aligning with the core definition of conceptual art.

Originating amidst significant social upheaval, the core principle of Conceptualism—that the idea reigns supreme—found broad application among artists seeking to highlight diverse social issues.

Conceptual Art, despite its transformative impact within the art world, remained somewhat esoteric and had limited resonance beyond artistic circles due to its perceived complexity.

Moreover, fractures within the movement surfaced by the mid-1970s, ultimately leading to its dissolution. Nonetheless, Conceptualism served as a wellspring of inspiration for subsequent generations of artists, many of whom interrogated the material foundation of art and the lexicon of visual culture.

In contemporary practice, Conceptualism has evolved into what is often referred to as Post-Conceptual Art and/or Neo-Conceptual Art.

While the distinction between these categories is subtle and overlapping, they represent different historical epochs. Post-Conceptual Art, originating in the mid-1970s, encompasses all art influenced by the Conceptual Art movement, spanning diverse mediums such as oil painting, sculpture, photography, and installation art.

On the other hand, Neo-Conceptual Art emerged in the 1980s and persisted into the 1990s, focusing on conceptual installation artworks following the dissolution of the Conceptual Art movement.

For instance, artists associated with the Pictures Generation, including Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Sherrie Levine, and Barbara Kruger, utilise traditional mediums like photography to deliver incisive critiques on themes such as originality, gender, and consumer culture, rooted deeply in conceptual frameworks.

Conversely, figures like the British-Indian sculptor Anish Kapoor align more closely with Neo-Conceptualism, infusing their works with profound conceptual undercurrents exploring metaphysical concepts such as absence and presence.

Works like Kapoor’s monumental “Installation View” (2020) use biomorphic forms of polished steel to evoke notions of transcendent connection between earth and sky.

Figures such as Tracey Emin straddle both categories, although she herself shuns such labels. Emin’s “My Bed” (1998), a raw and autobiographical readymade sculpture, lays bare her innermost self, offering a visceral exploration of personal identity, sexuality, and the human condition.

Contemporary Relevance - Shaping Current Artistic Practices

Conceptual art’s fingerprints can be seen across the vast landscape of contemporary art, influencing artists to delve into realms where ideas and concepts hold precedence over traditional aesthetics.

In today’s artistic milieu, conceptualism serves as a powerful tool for creators to challenge societal norms, question established systems, and provoke thoughtful discourse through their works.

Notable contemporary artists like Ai Weiwei intertwine politics with poignant visual storytelling, while Yoko Ono continues to push boundaries with her interactive performances that blur the lines between artist and audience. This evolution of Conceptual Art showcases an ongoing dialogue between the past and present, inviting viewers to engage critically with the ever-changing dynamics of our world.

In a digital age marked by rapid technological advancements and global interconnectedness, contemporary artists like Jenny Holzer harness the essence of conceptualism to address pressing issues such as information overload, surveillance culture, and social justice.

Through mediums ranging from large-scale projections on urban landscapes to thought-provoking text-based installations in galleries, these artists redefine how we perceive art’s role in shaping society.

By embracing Conceptual Art’s legacy while embracing modern tools and platforms for creative expression, this new wave of visionaries ensures that the movement remains a dynamic force driving innovation within today’s artistic scene.

Conclusion: Reimagining Boundaries and Shaping Modern Perspectives

In conclusion, Conceptual Art emerged as a pivotal movement in the art world of the 1960s, challenging established conventions and redefining the very nature of art itself. It blurred the boundaries between idea and object, emphasising concept over aesthetic form.

From the first conceptual artworks to contemporary conceptual art practices, artists have continuously pushed the boundaries of traditional categorisations and engaged in critical dialogues about the role of institutions, the commodification of art, and the relationship between art and society.

Whether it’s through conceptual photography, text-based installations, or collaborative group art projects, Conceptual Art has left an indelible mark on the art world, inspiring generations of artists to explore new avenues of expression and critique.

As seen in institutions like the Walker Art Center and the Whitney Museum of American Art, Conceptual Art remains an integral part of the contemporary art landscape, challenging us to rethink our preconceived notions and engage more deeply with the ideas and concepts behind the artworks themselves.

Unraveling the enigma of Conceptual Art has been a journey through the minds of visionaries challenging traditional artistic norms. From its humble beginnings as a rejection of conventional aesthetics to its evolution into a platform for thought-provoking social commentary, Conceptual Art has reshaped how we perceive and engage with art.

By emphasizing ideas over craftsmanship, artists like Sol LeWitt and Yoko Ono have pushed boundaries that once seemed immutable, paving the way for future creators to explore new realms where concept reigns supreme. This movement’s enduring impact lies in its ability to blur the lines between artist and audience, inviting us all to ponder not just what art is but what it can be.

As we reflect on the trajectory of Conceptual Art, it becomes evident that its influence extends far beyond gallery walls; it seeps into our collective consciousness, challenging preconceived notions about creativity and representation. By democratising art-making processes and questioning established hierarchies within the art world, this movement has inspired a generation of artists to break free from constraints imposed by tradition.

Moreover, Conceptual Art continues to serve as a catalyst for discourse on broader societal issues—from identity politics to environmental activism—proving that art has the power not only to mirror reality but also ignite change. In essence, Conceptual Art isn’t merely about creating objects d’art; it’s about forging connections between minds in an ever-changing cultural landscape where innovation thrives on introspection and dialogue.