French Impressionist Landscape Painting

The narrative behind Impressionist landscape paintings transcends mere vibrant colours and the depiction of nature’s ephemeral beauty, representing a profound exploration of the fine art medium.

It’s a saga of rebellion and the dawn of Modern Art, marked by a departure from entrenched artistic conventions towards the embrace of impressionist landscape art.

Rejecting the rigid rules established by Renaissance masters of the 16th century, Impressionists sought to faithfully represent their immediate perceptions.

If a lake appeared pink at dusk, they painted it pink—a bold departure from the established norms of subject hierarchy and color choice.

Moreover, the Impressionists were driven by a dual imperative: to capture the evolving world around them and to embrace the technological advancements that were reshaping society, marking a significant shift in the medium of painting.

Innovations like collapsible metal oil paint tubes empowered artists to venture outdoors, painting en plein air.

In doing so, they not only immortalised the natural world—its beaches, mountains, and changing light—but also introduced novel subject matter, depicting the everyday lives of laborers and the leisure pursuits of the bourgeoisie.

Thus, the history of Impressionist landscape painting is not just a chronicle of artistic innovation, but also a reflection of societal transformation and the democratization of art, symbolized by the embrace of open-air painting and the production of art prints that made art more accessible to the public.

History of Impressionism

Influential landscape artists such as Corot and Boudin greatly impacted young Impressionist painters.

While Corot created numerous oil sketches outdoors, they found little market during his lifetime, as the paintings he exhibited and sold were typically completed in the studio, yet his approach laid the groundwork for the impressionistic movement and the eventual acceptance of plein-air painting. In contrast, Boudin embraced plein air painting, completing his landscapes entirely outdoors, which is a technique central to the Impressionist style.

In 1841, an American artist revolutionized the art world by inventing collapsible metal tubes for oil paints, enabling the Impressionists like Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley to more easily paint landscapes directly from nature.

For Impressionist painters, who frequently worked outdoors, this innovation was indispensable. Concurrently, the expansion of railways was making the countryside more accessible, with new lines linking Paris to Normandy and towns along the Seine, which became both home and inspiration for many Impressionist artists.

Our enduring image of these painters depicts them outdoors, their hats shielding their eyes, with easels set up along riverbanks as they captured the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere on the landscape.

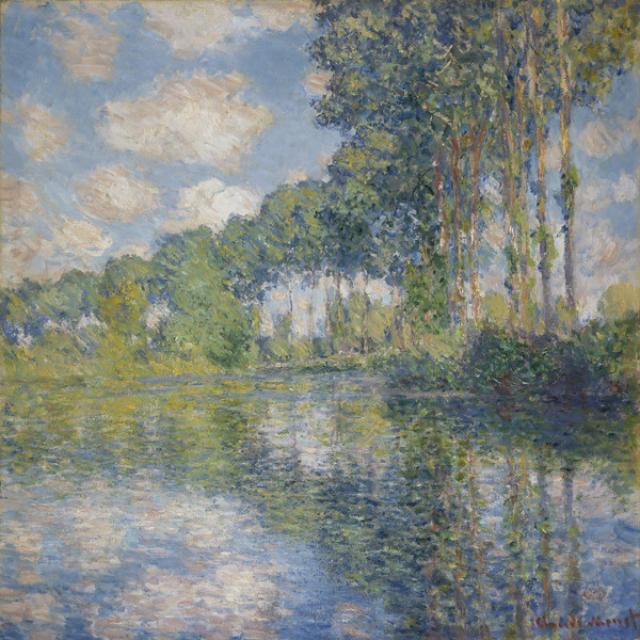

By around 1870, Impressionists like Pissarro, Sisley, Monet, and Renoir had embraced open-air painting as a cornerstone of their practice, frequently capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere on the landscapes surrounding Argenteuil.

When questioned about his studio, Monet famously gestured towards the Seine and its banks covered in buttercups, declaring, “That’s my studio.” While this depiction of Impressionism may contain elements of myth—many artworks bear signs of studio work—it underscores the importance these artists placed on direct observation, swiftness, and spontaneity as they sought to capture the ever-changing moods of weather, seasons, and times of day.

By the mid-19th century, open-air painting had become an established tradition, although most artists still distinguished between oil sketches created outdoors and finished works produced in the studio.

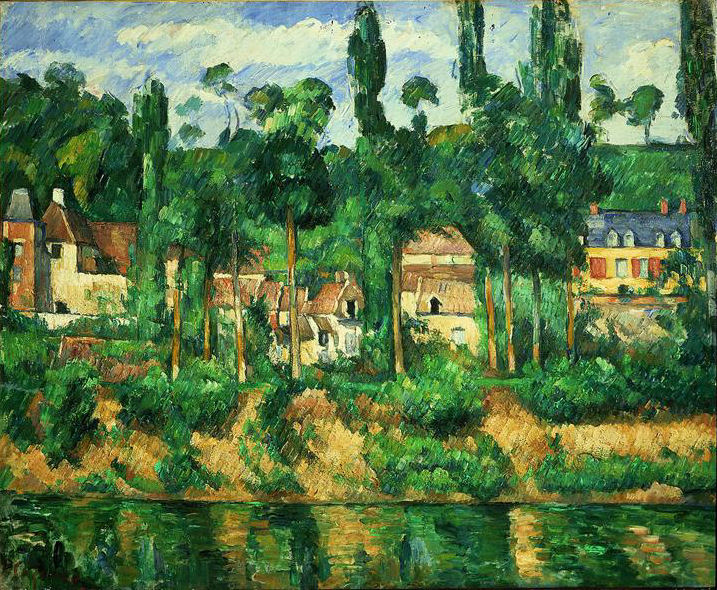

However, emerging bold painting styles were beginning to blur these distinctions. Realism, with its emphasis on truth, encouraged many artists to depict nature with unadorned directness, eschewing dembellishments or allegorical representations.

Impressionism and Progression – Influences on Impressionist Landscape Painting

By the mid-19th century, the practice of plein air painting had become entrenched in artistic tradition.

While most artists maintained a distinction between outdoor oil sketches and final studio works, a bold shift in painting approaches emerged, highlighting the importance of Impressionist style in landscape art.

Dissolving the boundary between rough sketches and idealized landscapes, artists turned their focus towards portraying the ‘truths’ of the world, diverging from the historical emphasis on myth and allegory.

This rebellion challenged the notion that painting should transcend reality.

For Impressionist luminaries like Claude Monet, often hailed as the movement’s progenitor, the plein air works of Gustave Courbet, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Eugene Boudin served as profound inspirations.

Boudin, notably senior by almost two decades to most Impressionists, profoundly influenced Monet’s artistic evolution with his emphasis on spontaneity and his practice of painting landscapes in an open-air setting.

Boudin famously stated that three outdoor brushstrokes held more value than days spent in the studio, emphasising the vitality of capturing a moment’s essence, which was a principle that underpinned the impressionistic approach to open-air painting.

His depictions of beach scenes and middle-class life eschewed overt narratives, instead honing in on the fleeting spirit of a particular day.

Similarly, Gustave Courbet shattered past conventions by championing a fresh approach to realism.

His renowned work, “The Painter’s Studio,” and numerous portrayals of peasants introduced original subject matter previously sidelined in the art world’s hierarchy.

Courbet’s daring vision challenged artistic norms, paving the way for Impressionists to redefine the boundaries of painting.

Significance of Initial Impressions

The Impressionist movement held historical significance by mirroring the profound shifts occurring within European culture. Claude Monet’s paintings, imbued with an underlying current, epitomised the exploration of colour perception—a pivotal aspect of the movement.

This exploration manifested in the vibrant hues directly applied from tubes and the juxtaposition of colours on the canvas rather than meticulously mixing on the artist’s palette.

Driven by an insatiable curiosity about light and its nuances, Monet’s landscape works stand as exquisite examples of temporal change.

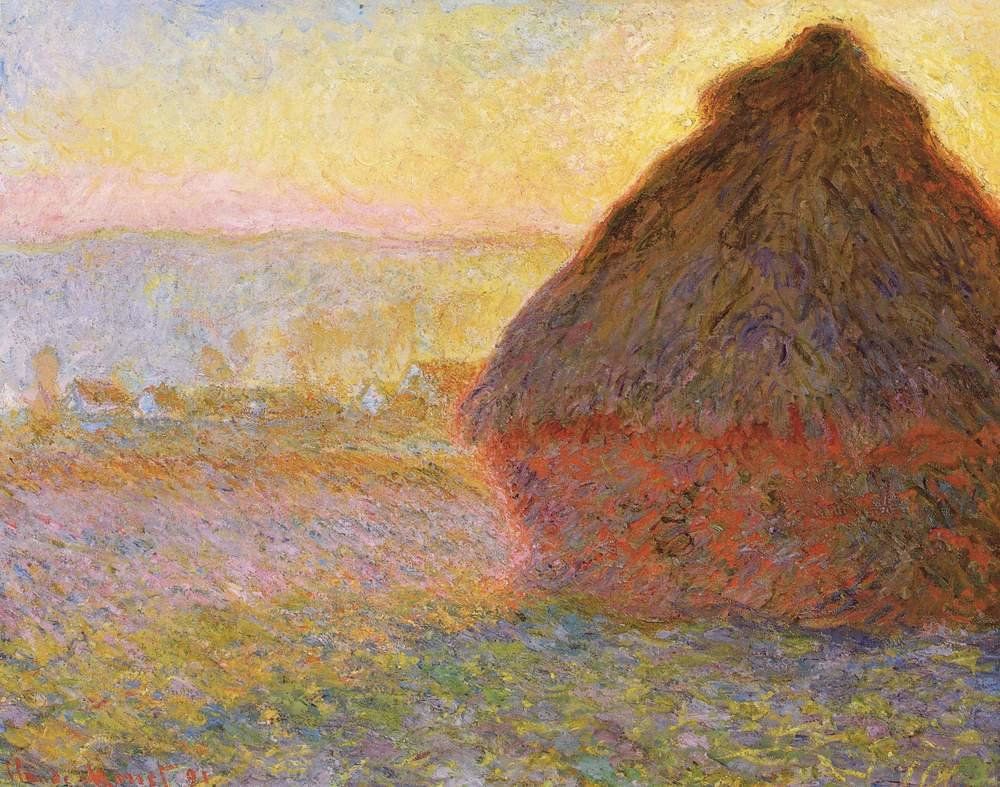

Often creating series of the same subject, such as his renowned Rouen Cathedral pieces, Monet’s approach hinted at the emergence of abstraction in art. His paintings eschewed a polished finish, earning the movement its distinctive name.

Monet’s method prioritised capturing the initial impression of a scene, underscoring the significance of direct observation, swiftness, and spontaneity.

Consequently, loose brushwork, vibrant palettes, and depictions of everyday life became hallmark traits of the period’s artistic style.

The Influence of Impressionist Landscapes on Later Developments

In his artistic evolution, Monet began to explore loose paint handling, vibrant colors, and unconventional compositions in places like Argenteuil, catching the eye of pioneering abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky.

Kandinsky, upon viewing Monet’s Haystacks series exhibited in Moscow in 1895, remarked that the subject matter only became apparent to him through the titles of the works.

This revelation underscored the shared aesthetic interests between the visual language of the time and subsequent abstract movements.

The fascination with light and color sparked inspiration among Post-Impressionist artists, who integrated various symbols and drew from distant and primitive cultures, as seen in the works of Paul Gauguin.

These new paintings became arenas for experimentation and change, echoing the Impressionists’ call for novelty. This spirit of innovation also captivated the renowned Pablo Picasso, whose groundbreaking images forever altered the landscape of art.

The tradition of landscape painting holds immense significance, serving as a conduit for artists to express their innermost desires or, in the case of Impressionism, their initial impressions and contemporary scientific inquiries. While Realism painting persists, it is to the innovations of major avant-garde movements that contemporary art owes its inception and evolution.